Ah, Pho! Finally, in our in-depth exploration of iconic meals from around the globe, we get around to talking Pho or humble Vietnamese noodle soup turned world-renowned comfort food. For those not in the know, we’re talking an absolute cornerstone of Vietnamese street food culture here: steaming hot, fragrant and aromatic broth served atop rice noodles, topped with plenty of fresh herbs, vegetables and meat.

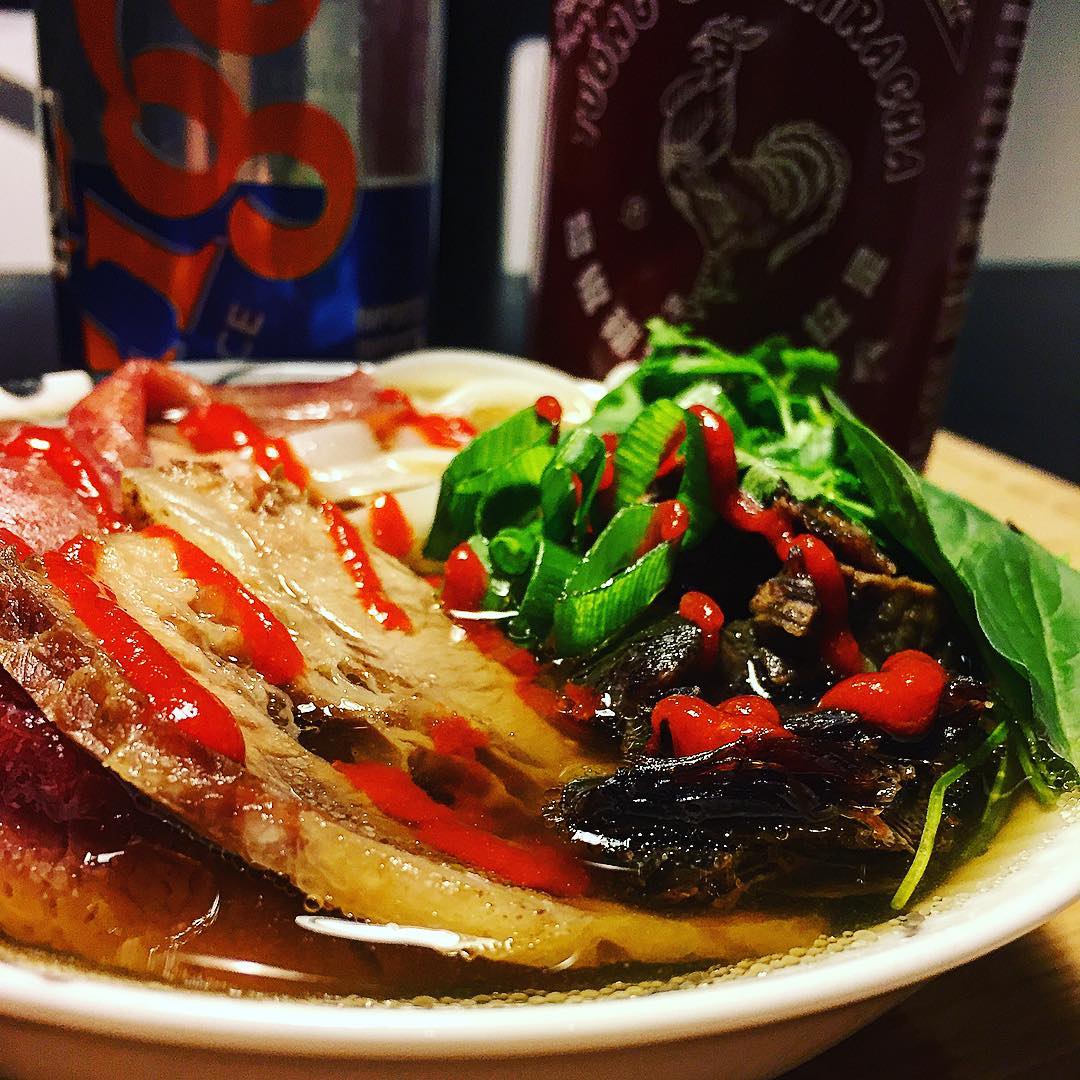

It is a comforting, wholesome meal that is at one time full of intense beefy depth and richness while at the same time containing an explosion of vibrantly fresh, bright flavors and a reassuring kick from the near obligatory squirt of lime juice and Sriracha chili sauce that serves as icing on the cake – as far as soups go, really, it’s about my favorite in the world!

Generally available in two different varieties featuring either a beef or chicken base, Pho is an inexpensive, nutritious and filling meal originating from Vietnamese street kitchens where it was typically enjoyed by people of all walks of life – usually while on their way to or from work or during well-deserved lunch breaks. From such humble beginnings, the dish spread across the world with Vietnamese refugees fleeing the atrocities of war and persecution and has in the past 20 years experienced a massive surge in popularity not unlike that of its Japanese comfort food cousin: ramen!

Today, we dissect the history, origins and composition of Pho – Vietnam’s most popular comfort food turned international smash hit in hipster kitchens from LA over London to Melbourne, we explain the basics and secrets of Pho, and we draw up our own perfect version of the tastiest and arguably more popular Pho version: Pho Bo, or Beef Pho.

Before we get started, though, let’s clear out something that has been on a lot of people’s minds to the point of actually sparking heated debates:

What the Pho: How to properly pronounce Pho

For as long as Pho has been found outside of its native Vietnam, people have managed to mispronounce the simple three-letter combination of p, h and o. Most westerners, excusably so, pronounce it pho, as you would if it were to rhyme with dough, or say a less flattering name for a loose American woman. Because that’s generally what makes sense given our consensus on the subject of phonetics. In its native Vietnam, Pho is, however, pronounced fuh with a distinct u sound: Fuh! As it pho-king good, see!

So bear in mind, kids, if you want to impress all your fellow foodies in the culinary school yard – at the risk of confusing everybody else – you’ll pronounce it fuh. Do so clearly and precisely, though, lest you end up like Malou and I when speaking on the phone last night… “What are you prepping for the blog,” she asked me. “Pho,” I told her truthfully. Static on the line, however, warped my perfectly pronounced fuh as “wha?” after which the conversation took on the state of bit of an endless loop.

So, yeah, personal anecdotes and jokes aside, please take note, fellow culinary traveler: It’s fuh, not foe! Why is this important? Well, for starters there’s absolutely no need to fight over noodle soup (we’ll make enough for everyone), secondly the pronunciation may help shed some light over the culinary history of this iconic dish and help validate one of many origin myths surrounding it.

History of Pho

The history of Pho and how it won its place amongst the most internationally renowned dishes is complicated to say the least. Pho is distinctly Vietnamese in origin, but like so many other Asian dishes shaped by migration, colonialism and other outside influences. And not unlike most other dishes we’ve looked at, the origins are sketchy. The dish itself is first referenced at the beginning of the 20th century and is thought to have originated in the Nam Định Province southeast of Hanoi.

They call it soup… But it’s more of full-blown a meal in a bowl, really…

While most culinary historians agree that the dish has existed in some form or another well before that time and even well before the arrival of French influences, many culinary historians argue that Pho would not be Pho as we know it today had it not been for the influence of some very French colonial overlords and a bit of a surprise influx from Chinese migrant workers.

Pho history: The French Connection

From the paté-smeared baguette used in the country’s signature Bánh Mi sandwich to an unnatural obsession with pastries, French influence on Vietnamese culinary history is everywhere. Even in Pho, a seemingly very Vietnamese dish. Had it not been for the French, chances are that there would be no such thing as a world-renowned Vietnamese Sriracha delivery vessel noodle soup – or other Vietnamese beef-based dishes for that matter.

Beef consumption, you see, was practically non-existent in Vietnam prior to the arrival of the French, for one simple reason: Cattle, to a generally less than affluent farming/working class community, were much more valuable as a source of labor than a source of sustenance. Consequently, the Vietnamese, historically preferred pork and chicken over beef when it came to animal-based protein.

With the arrival of the adorably savage and hedonistic French, however, came not only a wealthier upper class but also foreign food culture which relied heavily on the systematic breeding and slaughtering of cattle for consumption. In a country with a large social divide, the best cuts of the steer obviously made it to the wealthy but even so, a lot could be done with the less desirable cuts and odd ends left behind, and one such application was Pho.

Granted, early Pho recipes were probably nothing like the elaborate and oversized meals we see today. It was decidedly poor man’s food, street food for the masses – for workers and for farmers. The beauty of broth-based soups is that they carry all the flavor of the scraps used to produce them along with an inherent heartiness from the bones and connective tissue. With the simple addition of nothing more than a handful of noodles and some aromatics, herbs and spices, Pho eventually became an easy way of turning bones, scraps and odd ends into an affordable, nourishing and filling meal for the native working class.

Pho history: The Chinese influence

Being that the Vietnamese had little tradition for cooking with beef, it is argued that the next major leap in the popularization of modern Pho was taken not by the Vietnamese, but by Chinese migrants. Chinese workers would purchase beef bones from the French and cook them into a Chinese-inspired dish similar to modern Pho known as ngưu nhục phấn. This dish initially gained popularity with workers sourced from the provinces of Yunnan and Guangdong as it reminded them of home, but rather quickly gained foothold and became a staple amongst the general population. And so, somewhere in the melting pot of French colonialism, Vietnamese tradition, Chinese influences and pure necessity, it is said, modern Pho was born.

Pho history: International popularity

Rather ironically for a dish born in a somewhat depressing mix of colonial influences and a longing for home, it took much greater tragedy for Pho to reach the international acclaim that it enjoys today: the horrors of war!

Initially popular in Northern Vietnam, Pho enjoyed little if any popularity in the South, that is until 1954 brought the partition of the country into North and South. Over a million refugees from the north poured into the south, bringing with them their love for Pho. Pho, through tragedy, had claimed the nation. It did not, however, stop there.

In the aftermath of the war, several million refugees poured into the world, again bringing with them their love of what had become an absolute staple. Restaurants specializing in Pho started popping up in Vietnamese enclaves around the world. In the early 1980’s, the first Pho restaurants opened in California and the rest, they say, is history: Pho exploded into the mainstream, starting on the West Coast but quickly seizing the East Coast as well and spreading evenly across the country to a point where Pho restaurants are said to have generated an estimated $500 million in annual revenue in the early 2000’s.

Pho history: How did Pho get its name?

And so, rather ironically, and completely disregarding all its inherent atrocities, it can be argued that French colonial influence of Vietnam may have helped nurture the working class and, in the process creating some of our modern world’s most recognizable dishes like the Bánh Mi Sandwich and, of course, Pho. So strong is the French influence that some etymologists actually argue that the name itself, Pho, is a deliberate culinary reference to the French stew Pot-Au-Feu, the name of which literally translates into pot-on-the-fire.

This claim, however is disputed by others arguing (quite fairly so) that Pho shares very few similarities with pot-au-feu – except itself and the fact that the dish was traditionally cooked in pot on the fire. The name, they argue, is short form of lục phở which again was a corruption of the Cantonese-inspired dish ngưu nhục phấn referenced above.

Which is correct? We may never know! All we can say for certain is that Pho is not decidedly Vietnamese in origin or naming, but is now an important part of Vietnamese culture and heritage… And it’s delicious! So, let’s go ahead and make some Pho!

Homemade Pho: What makes a great Pho?

Before we get started, though, I’m sorry, but we’ll have to cover a few basics about how to make and serve the perfect bowl of Pho. We’ll start with an overview of what cuts of beef make the best broth, we will discover the easiest ways of turning these chunks into a perfectly clear broth and even cover aromatics, fillers and garnishes.

What separates good Pho from run-off-the-mill Pho, you see, is an understanding on the part of the chef of the ingredients that go into the dish and how to treat them properly. Reading these paragraphs will help you achieve from day one the goals of any aspiring Pho-maker: A rich, fragrant and aromatic broth that is both crystal clear and intensely beefy – every damn time!

When you read these words, fear not: Making Pho is not a half hour process, but neither is it a particularly difficult one. Once you understand the key concepts which we will cover in detail below. Most of the actual work of making Pho is in the early stages of the game; in sourcing the ingredients, understanding the basics and creating the broth. These basic concepts take a bit of time to understand and execute, but essentially, creating one serving of Pho is about as labor-intensive and lengthy a process as creating say ten or twenty servings. So take your time, grab a few beers, get to understand the process, follow the guidelines and make yourself a big-ass pot of Pho! Whatever you can’t consume in one sitting freezes easily.

Perfect Pho: Best cuts of meat for a flavorful broth

By far the most important element of Pho is a rich and intensely beefy broth. Traditionally, Pho was poor man’s food and served to exploit the bones of an animal. In today’s more prosperous world, Pho has evolved into a slightly more elaborate dish that is often made with one or more flavorful and expensive cuts of bone-in beef, all with their own unique flavor and purpose and some of which contain meat scraps that can be served in the soup for extra flavor and texture. Pho broth is now traditionally prepared from one or more of the following chunks of cow: beef shank, ox tail or beef bones either of which add their own unique touches to the broth.

Bones, ligament, connective tissue and fat… All good stuff when it comes to making broth!

Beef shank: You may remember beef shank from our popular Osso Buco recipe where we used them to add flavor and richness to a classic beef stew. In that case, and in this case as well, we picked beef shank for a few very good reasons: beef shin bones, which compromise a considerable part of the cut, contain bone marrow that will add considerable amounts of flavor and enrich the soup during cooking. The meat surrounding the bone contains a lot of connective tissue which besides also adding flavor will dissolve into gelatin during cooking, creating an even richer broth with silky mouthfeel. And, finally, besides bones and connective tissue, they contain a fair amount of succulent meat which can be cubed or shredded after cooking, then added back to the soup for a more decadent, filling meal. If you were to use only one cut of beef for Pho, beef shank would probably be it! But hey, why settle for just one when there are several other good options?

Ox tail: Ox tail is a favorite Pho cut for many. Richer than beef shank in flavor and beefiness but also much more expensive. A cow, after all, has four legs but only one tail. Unlike beef shank, ox tail does not contain bone marrow but offers a lot more connective tissue which again translates into a richer broth and much better, much more tender meat. Here’s the thing about ox tail meat, however. It’s pretty densely packed around the bones and unless you really enjoy munching on soft connective tissue and cartilage, (I personally don’t, but it’s not a crime, people!), you will be spending some time picking off the bones and separating scraps of connective tissue from melt-in-your mouth tender beef chunks before serving. The extra time (and money), however, is pretty well-invested when it comes to flavor, mouthfeel and decadence.

Beef bones: Beef bones were the traditional choice for the Pho cooks of yore. For one very simple reason: affordability! Mere bones offer less flavor and richness than either of the above, but at a fraction of the price. If you’re cooking a large pot of Pho (and, honestly, why wouldn’t you?), I definitely recommend using a fair percentage of beef bones in the broth mix to cut costs. For perfect results, try to get your hands on sawed-through leg bones or shoulder/knee joints (usually available in bulk at your friendly neighborhood butcher or supermarket) as they offer more flavor owing to the considerable amount of exposed marrow they contain. Also, never shy away from bones with pieces of meat and/or connective tissue still attached. It’s all great flavor and flavor is what we want in our broth. Basically, the more macabre the bones, the better the broth.

So, with at least three good choices to go by, which should you chose? The all-round and slightly expensive, the decadent and expensive or the classic, utterly inexpensive option? As stated above, if using only one cut, beef shank would be a pretty solid choice in terms of price vs flavor. My solution, however, as the chronic crowd-pleaser that I am, is to go with a mix of all of the above, as all cuts bring distinct flavors and advantages to the party. And I usually go with a 1 – 1 -2: One part ox tail to one part beef shin and two parts beef bones. This combination, I feel, offers the perfect richness, the perfect intensity of flavor and the perfect amount of bonus meat for a reasonably fair price. Your perfect mix is entirely up to you, of course, and experimentation is encouraged. As long as you end up using about the same amount of bony cuts by weight, the recipe below will work.

Beef Pho basics: Beef filling

So, we’ve got the basics of our broth down and we’ve even got some leftover scraps to add body to our soup. What more could we want? Well, it seems that modern Pho has evolved a bit from its humble beginnings into somewhat of an elaborate and more filling meal. What I mean is that a modern bowl of Pho, particularly if served in the West, will often contain a stunning array of meaty fillers, including but not necessarily limited to:

- Any edible scraps and pluckings that remain from the bony beef bits used to produce the broth.

- Slices of a tough, flavorful cut like brisket or shoulder that cooks slowly in the broth and is then sliced and served in the soup.

- Tender cuts of beef that are sliced paper thinly and placed raw in the bowl as a garnish prior to service, then flash cooked by the addition of the hot broth.

Naturally, such procedures divert a little from the humble poor man’s origins of the dish and some leave them out citing monetary and authenticity reasons. In my version, I’ll include a trifecta of meat. Whether you’ll want to include them or leave them out, I’ll leave to your discretion. Think of the recipe below as luxury Pho that can be easily made less extravagant.

Right, assuming then that we’ve got beef shank or ox tail as part of our broth base, we’ll need two additional cuts of meat to finish our Perfect Pho. Feeling that your poor man’s soup is already expensive enough from all the shank and ox tail? Simply skip this part!

Beef Pho basics: Use brisket for texture

When it comes to this part, your choices are many. Basically, you can use any hunk of meat, that benefits from slow cooking and low temperatures and cooks up relatively firm and textured. I personally like the taste and somewhat firm texture of brisket while others swear by beef shoulder. Some even go as far as suggesting a combination which seems a bit overkill even to me. I’d say pick one and stick with it, then use scraps and pickings from beef shin and ox tails as a supplement. Again, I really enjoy the texture of brisket – it retains moisture well during cooking and slices well, it offers texture and resistance to bite without being chewy, and is easy to handle and eat using either of the traditional methods of Pho attack: chopsticks and spoons. Again, the choice is yours, but since the shin and tail meat is nicely soft and tender, why not try a bit of slightly densely textured brisket with your rich and mouth-coatingly delicious Pho? Just saying…

Beef Pho basics: Raw meat for garnish

In addition to its base combination of beef bones and stew meat, Pho is often served with a garnish of thinly sliced raw beef. Because who doesn’t like a bit of raw meat with their meat? Oh, wait… Not a fan of raw meat? Fear not, the general idea behind this type of garnish is that upon serving, the steaming hot broth will easily flash cook the thin slices of beef to a nice state of medium-rare to medium depending on how hungrily you chow down on your soup.

Can’t stand raw meat? You can skip this step, or simply soak it properly in the broth to allow it to cook through…

Again, your choices of beef are many. Pho tracing its origins back to a cheap peasant’s dish, slices of inexpensive yet massively flavorful flank steak is probably the most traditional of choices. If you want to dress things up, you can use anything from sirloin to tenderloin, just bear in mind that the more expensive and tender the cut, the less flavorful it will be. In a rich, flavorful broth, an expensive cut like tenderloin would literally drown and would probably seem an utter waste of money. Flank works much better here, but I personally save that for Carne Asada (an entirely different post) and favor thinly sliced sirloin as we know it from Carpaccio when it comes to Pho. It offers a nice balance between price, decadence, flavor and texture, I feel.

To sum up: To create our perfect Pho, we will need two parts of beef bones to one part ox tail and one part beef shin (exact measurements follow) for our base broth. Also from the meat department, we will need a relatively small piece of beef brisket (substitute beef shoulder at your own risk) and eventually 3-5 slices of very thinly sliced flavorful beef like flank or sirloin per diner… And now, with that out of the way, we’ll need some additional flavorings as well. Let’s move on to the second-most important part of the Pho equation!

Perfect Pho: Spices and aromatics

Where other Asian cuisines rely heavily on bold flavors like garlic, chilies and soy, Vietnamese cuisine is generally based on much milder, much more subtly fragrant flavors like fresh herbs, ginger, fish sauce and earthy spices like cardamom, cinnamon and star anise. The result are dishes that are less in your face aggressive than the dishes of other Asian countries but rather subtly and deeply aromatic – and Pho is a perfect example of one such dish.

It begins with the broth which is initially flavored with bits of onions and ginger that have been perfectly roasted to take off most of their raw edge and add a subtle sweetness. These two main aromatics of Pho are added to the broth as it comes to a simmer along with traditional spices like cinnamon, star anise, fennel seeds, cardamom and cloves to create an earthy, citrusy, floral, sweet and incredibly aromatic and savory broth. The entire thing is then simply simmered for about six hours to overnight before being ready for serving and garnishing with a burst of fresh herbs and other bold and bright flavors. Well, okay, it’s a little more complicated than that, but not much, let’s have an in-depth look at the process of creating the perfect broth for Pho.

Perfect Pho: Secrets to a clear broth

The benchmarks of a perfect pho, besides an abundance of flavor and richness, is a perfectly clear broth. A perfectly clear broth is something that professional chefs, street cooks and home cooks alike spent years of trial and error to achieve and there are two general schools of achieving perfect results. It is, in essence, everything. To the layman, it creates a much more attractive product, to the Pho aficionados and the culinarily initiated, it signals: This person knows how to cook, I should have sex with said person! … Ummm… or something along those lines!

Now, ahem, if we want a clear broth, we first need to understand what sometimes makes a stock murky. Stocks grow murky essentially because the beef (by)products we boil to produce them contain various impurities. As our stock simmers, these impurities will coagulate and rise to the top of the pot in form of foamy, murky, greyish matter. All, and I do mean all, of this murky grey mess must be eventually removed lest it emulsifies back into the stock creating a perfectly tasty but murky concoction that does not translate well into soup base.

When it comes to removing these impurities, there are basically two schools: the traditional slightly weird French method and the slightly weirder and more rock ‘n’ roll Vietnamese. In classic French stock making (check out my post on the subject here), a clear broth is achieved by meticulously, continuously and carefully skimming the stock as it simmers, all impurities that float to the top. This process requires skill, dedication and attention and it is often followed by careful straining of the stock through a fine meshed sieve or cloth and a slightly unappetizing process in which the stock is laced with raw egg yolks and chopped meat then brought back to a simmer until the egg whites and meat proteins form a discardable mesh that effectively trap any remaining impurities, leaving behind an entirely clear broth, known in French as a consommé.

… And then there’s the Vietnamese way: Parboiling! In this seemingly unorthodox method, the beef and bones needed for the stock are first brought to a rolling boil for a good fifteen minutes which will cause most if not all impurities to coagulate quickly, creating essentially a pile of messy bones swimming in a sea of gritty scum. The scum is then discarded along with the water after which the bones are poured into the sink and thoroughly rinsed in cold water, returned to a perfectly clean pot, covered with fresh water and then carefully simmered and skimmed for hours on end. This processes, supposedly, create a perfectly clear broth with a lot less work than the traditional French method. In your FACE, colonial overlords!

How’s that for clarity…?

Now, I realize that to western minds, this process sounds terrifying and wrong, but the Vietnamese have been doing it for a century and it supposedly just works, creating a broth that is not only clear, but also deeply flavorful and rich. Coupling this with the reassuring words of J Kenji López-Alt that very little flavor is extracted and lost in this fifteen minute roaring boil, I decided to give this bad magic approach a try. With trembling hands, I brought a pot of bones and beef to the boil only to find out that yes, a very large, nasty mesh of scum, coagulated proteins and other goodies did indeed form at the top of the pot. I then dumped everything into my (thoroughly cleaned) sink and felt like a right idiot washing and scrubbing bones and meat scraps for a good ten minutes.

Feeling a right heathen, I returned the bones to the pot, added the traditional aromatics and spices, brought to a simmer and about dropped my jaw on the floor. Not only did the pot require very little attention and skimming during cooking, but after about six hours on the stove, I had a complete success at my hands:

A broth that was not only perfectly clear but also incredibly rich and flavorful. All it needed was a light skimming to remove excess beef fat and it was good to go. No flavor loss or impurities, au contraire, mes amis! I’ll be damned.

Perfect Pho recipe: How to make perfect Pho at home

This, of course, all seems fine and dandy. But how, pray tell, do we go about making some at home. And won’t it be terribly difficult? Well, here’s the good news, once you’re done with the broth, you’re basically done with the dish… And, uhhh…

Granted, making stock at home will not be the simplest of culinary projects you can undertake. However, this entire process may seem like a hell of a lot more difficult than it actually is! Again, fear not, young grasshopper: it may be time consuming, but if you stick to our rogue broth-making method outlined above and detailed below it’s definitely neither difficult nor particularly labor intensive. And, really, if you’re this far into the read, who are you to be scared by lengthy cooking procedures?

Besides, as a loyal reader told me not long ago: I’ve learned a long time ago to always go with Johan’s recipes; they allow for, and encourage you to have a few beers while cooking! (Thanks, Kamilla, glad to have you along for the ride!).

Mmm… Beer!

And, again, here’s the kicker: Once you’ve made the broth, you’ve basically made Pho! Much of the beauty of this dish lies in the fact that it is garnished and seasoned tableside – according to the diner’s personal preference. You provide the broth, the noodles and the garnishes and then it’s completely up to your guests to make it fit their taste buds. How? Well, it’s quite simple, really:

Serving Pho: Pho garnishes

Assembling a proper bowl of Pho can be a bit of a jigsaw puzzle, consisting of fillers and garnishes, cleverly brought together by the broth itself. It is, however, also great fun as you get to tailor your meal to your exact preferences and even adjust as you go. The general rules are few and playfulness is generally encouraged here.

The main filling element is, of course, noodles and with Pho, we divert a bit from the noodle soup norm in that Pho, unlike many other noodle soups, is served over rice noodles. Rice noodles are a staple of southeast Asia and are, as the name suggests, made from rice flour rather than wheat flour.

Like wheat-based noodles, they are usually packaged and sold in a dry form but unlike wheat noodles, they are prepared by reconstitution rather than boiling. Water, either hot or cold, is poured over the noodles and they are simply left sitting until soft, pliable and ready to eat. The unique ingredients and preparation method gives them a more unique flavor along with a denser, chewier texture that makes them perfect for soups or sauce dishes like Pad Thai. Oh, and speaking of soups and saucy dishes, you’ll need to know that much like pasta, rice noodles are available in several shapes and forms, and just like pasta, it’s the desired application that dictates the shape of noodle used. For Pho, you’ll strive to get noodles of the appropriately named Banh Pho variety which you’ll easily recognize by their distinct flat shape.

A bowl of pho accessories… Ready for the broth!

Banh Pho come in different sizes from a thin version the size of flat linguini to a medium version to a broad version that basically looks like rice fettucine. For soups, you’ll want to strive for the thin to medium sized noodles while the broad version is generally used for stir fries and heavily sauced dishes like Pad Thai.

That being said, if the right form is not available, you can use whatever shape you like, as the attentive reader will see I’ve had to do for the purpose of this post. So, in short, do as I say, not as I did. And if in trouble, substitute!

Now, as far as garnishes go, the soup itself is seasoned upon serving with an abundance of herbs – basil, mint and sometimes cilantro are traditional, but others are often used. Bean sprouts are added for an additional fresh, herbaceous punch along with the meat scraps salvaged from the cooking process and any other meats that may have been added during the cooking process. These traditional toppings are simply plunked into a bowl and topped with soup to release an explosion of flavors and aromas.

More pungent yet traditional toppings such as lime juice, chili and hoisin sauce are usually served on the side and applied at the diner’s discretion, allowing her to first appreciate the natural richness and subtly spicy/herbaceous intensity of the soup before applying bolder flavors such as my beloved Sriracha.

Perfect Pho Recipe - Vietnamese Noodle Soup

Authentic recipe for Pho - Vietnamese Noodle Soup

Ingredients

- 2 pounds beef shank

- 2 pounds oxtails

- 4 pounds beef bones

- 2 large onions split in half

- 10 cm piece of ginger washed and split in half

- 1 cinnamon stick

- 4 star anise pods

- 1 teaspoon fennel seeds

- 1 teaspoon coriander seeds

- 5 cloves

- 4 cardamom pods

- 0.5 deciliter fish sauce

- 2 tablespoons palm sugar or light muscovado sugar

Garnish:

- 1 pack thin rice noodles Banh Pho noodles

- 4 large handfuls mix fresh herbs cilantro, Thai basil and mint

- 4 handfuls bean sprouts

- 4 scallions sliced

- 2 limes cut into wedges

- Hoisin sauce

- Sriracha

Instructions

-

Preheat oven to broil.

-

Place beef bones, ox tails, shanks and brisket in a large pot and cover fully with water, bring to a boil over high heat.

-

Meanwhile, place onion on ginger on a baking tray and broil on the top rack for about ten minutes until charred on one side, but not cooked through. Remove from oven and turn oven off.

-

Once pot of bones come to a boil, allow bones to cook at a rolling boil for about 15 minutes.

-

Carefully remove pot from the stove and boil entire content into the clean sink.

-

Thoroughly rinse bones, removing any remaining gunk or impurities.

-

Finally, give the pot a thorough cleaning, place the cleaned meat and bones back in along with the ginger, onions spices and fish sauce, then cover with clean water.

-

Return pot to the stove and bring to a simmer over high heat.

-

Once a simmer is reached, back down the heat and allow to simmer for about 90 minutes, taking care to remove any gunk that may float to the surface.

-

After 90 minutes, carefully remove brisket from the pot, allow to cool slightly, then refrigerate till needed.

-

Allow broth to simmer for at least another four hours before carefully straining into a clean pot or container.

-

If broth seems a little unclear, you can strain again through a very fine-meshed sieve or a piece of cloth to remove any remaining impurities.

-

Discard beef bones, ginger, onions and spices. Set beef shanks and oxtails aside until cool enough to handle.

-

Put strained stock over low heat, carefully skim most of the fat off the surface, then season to taste with fish sauce, salt or sugar and keep broth on a very low simmer till needed.

-

Once cool enough to handle, pick the meat from the oxtails and beef shanks, discarding any large pieces of fat or connective tissue in the process.

-

Remove cooled brisket from refrigerator and slice into half-centimeter thick slices.

-

Put two slices of brisket and a couple of teaspoons of shredded meat per diner into a small pot, ladle over a bit of the broth and keep warm on low heat until ready to serve.

-

Put rice noodles in a bowl, cover with water and steep according to package instructions.

-

Fetch one large bowl per diner. Lay one serving of noodles in the bottom of the bowl, top with herbs, bean sprouts, cooked meat and finally a few slices of raw beef.

-

Carefully ladle hot broth into the bowl and let diners watch in awe as the broth cooks the beef before their eyes. Then serve immediately with a side of lime wedges, Sriracha, Hoisin sauce and Asian beer, allowing diners to tailor their own experience by adding as much or as little heat as they desire.

Recipe Notes

This recipe (probably) makes more broth than needed. The broth freezes really well and can be easily thawed and re-heated whenver a Pho craving arrises!

And there you go: perfect Pho! The perfect comfort food, perfect cold weather food, or hot weather food, really, and perfect party food! Enjoy Pho by yourself as an easy weeknight meal, with friends or family as a bit of an exotic alternative to the usual steaks and potatoes dinner or with a bunch of people as easy and engaging party food.

First taste the broth… Then add Sriracha… A lot of Sriracha!

The options are many and Pho works especially well in crowds: diners can build their own dining experience and there are generally very few rules and regulations to building and enjoying a steaming bowl of Pho, however one reigns supreme: Respect the cook, respect the broth! As stated above, the main component of Pho is the broth and while the addition of overwhelming condiments like Sriracha is generally encouraged (link Mikey Chen), you should honor the work and talent going into the dish by tasting the soup before piling on pungent, optional condiments such as Sriracha, hoisin sauce and lime juice. It’s not only proper etiquette, it also helps you judge how much or how little rooster sauce to add… Wait, is there such a thing as a little Sriracha?

Either way, I hope you give this Southeast Asian comfort food classic a spin. It really is one of my favorite dishes in the world and while not exactly easy, it’s surely nowhere near as difficult to craft at home as some will have you believe!